By: Pilar Ortega

As the attending physician in the ED, I have already heard the case presentation from the resident. “Doctor,” the patient says, “there’s something wrong with my blood.” I notice the patient’s gestures, his hand movements. His filler words are ‘eh’ and ‘esto’ rather than ‘um’ or ‘well’, the melody of his speech not unlike the sounds of my own childhood. His facial expression tells me he is searching for a word.

“Dígame,” I offer, a Spanish term that is an invitation to tell me more. It takes him a moment to register the change in language, and when he does, he sits back and continues describing his symptoms, but this time in a seamless, natural and effortless rhythm, sometimes in Spanish, sometimes in English, depending on what feels just right.

“Could it be from the veneno in my blood, Doctora?” he asks. Confused by his question about veneno, the Spanish word for poison, I pull up a chair. My mental differential diagnosis starts to churn. Could he be ingesting a toxin? Could he be delusional? Could he be using the word in gest as a reference to one of his medica-tions and its side effects?

“Le enseño,” he says, using the word enseñar which means ‘to show’ but also ‘to teach’. He deftly pulls up the electronic health record on his phone and finds the panel of routine blood tests from his last check-up. He points to the term ‘venous blood’. For the next several minutes, I explain what the word ‘venous’ means in English and reassure him that the blood tests do not indicate poisoning.

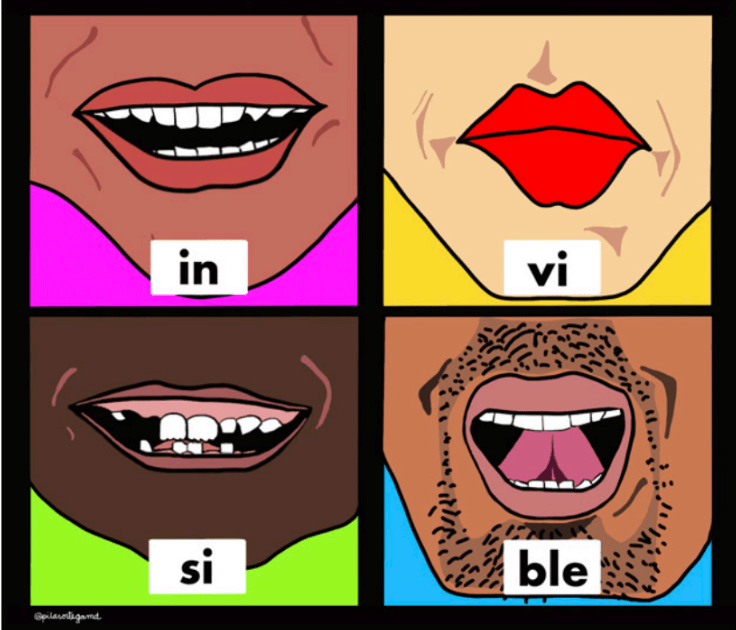

I discuss this encounter with the resi-dent, who, like me, has excellent proficiency in both Spanish and English. She is surprised not only about the new information the patient offered but also that the patient spoke to me in Spanish. As physicians, we are trained to address the patient’s chief concern, a skill that must be balanced with an understanding of the patient as a complex, whole person within a social context. Language pref-erence is an invisible yet core aspect of patients’ identity and a social driver of health outcomes. Yet, language remains hidden when health systems do not strategically collect, track or match patient and clinician languages or provide training in language- appropriate care. Even when social determinants of health are incorpo-rated into medical curricula, language is frequently left out. Figure 1 depicts four patients attempting to make evident what has traditionally been under-recognised and undervalued by mouthing the syllables of the word ‘invisible’ in their preferred language.

I discuss this encounter with the resi-dent, who, like me, has excellent proficiency in both Spanish and English. She is surprised not only about the new information the patient offered but also that the patient spoke to me in Spanish. As physicians, we are trained to address the patient’s chief concern, a skill that must be balanced with an understanding of the patient as a complex, whole person within a social context. Language pref-erence is an invisible yet core aspect of patients’ identity and a social driver of health outcomes. Yet, language remains hidden when health systems do not strategically collect, track or match patient and clinician languages or provide training in language- appropriate care. Even when social determinants of health are incorpo-rated into medical curricula, language is frequently left out. Figure 1 depicts four patients attempting to make evident what has traditionally been under-recognised and undervalued by mouthing the syllables of the word ‘invisible’ in their preferred language.

In the case of individuals with sufficient English to ‘get by’, their non- English languages are often rendered inconsequential. My patient had not been flagged as limited English proficient, nor should he have been. His language preference was a combination of both languages that is unlikely to be documented in the electronic medical record. In English- dominant settings, healthcare systems may centre English monolingualism and construe individuals with diverse linguistic practices as needing ‘extra’ accommodations. In effect, multilingualism is perceived as a deficiency and a burden rather than an asset.

Moreover, in any given encounter, both patient and clinician languagesmust be considered to determine how communication can be best achieved. However, clinician language data collection and certification processes are not standardised, making language an often-invisible attribute within the healthcare workforce. Adding to the complexity of linguistic identity, people are sometimes singled out in negative ways based on language, such as those with a perceived ‘foreign accent’ or whose name or physical attributes are—correctly or incorrectly—associated with certain languages.

Debriefing after this encounter, the resi-dent tells me stories of being pulled to serve as an ad hoc interpreter, stories to which I can relate. She has never before spoken with another physician about when or how to use her language or cultural skills to the greatest benefit of a particular clinical situation. She has never before worked with a Latina, Spanish- proficient attending. With Latinas comprising only 2.4% of active US physicians, this is not surprising. Our one shift together highlights what might have been missed and gone unnoticed—an invisible gap in the resident’s training or the patient’s care.

The clarification of the word veneno may seem like a minor win, but how many additional medical visits and unnecessary workups was this patient spared because he now understood his laboratory results? What are the health benefits of the reassurance he gained? And how many future patients will be impacted by the resident’s newfound insights about effective multilingual communication? With a record number of over 110 million forcibly displaced people world-wide in 2023, linguistic diversity is a daily reality in healthcare. For example, 21.7% of the US population (over 67.9 million people) and 8.9% of the UK’s population (over 5.1 million) speak a non-English language at home. Language-based dispar-ities result in invisible missed opportunities in teaching and care too numerous to count.

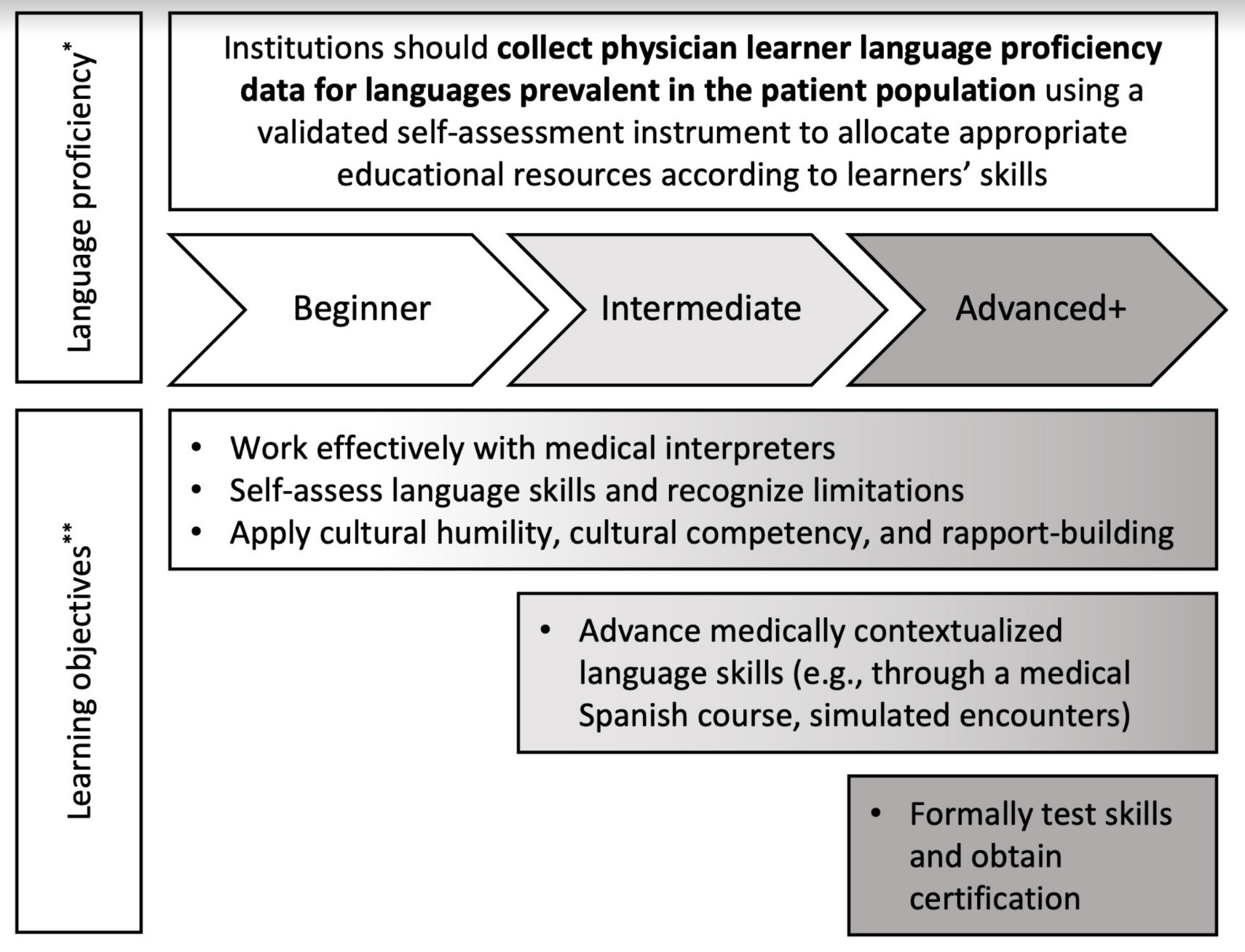

This case illustrates that even in the ideal scenario where the entire medical team shares the patient’s preferred language, if the language skills of each team member have not been adequately addressed, things can get missed. It is a common misconception that multilingual learners are intrinsically equipped with the ability to apply the medical skills they have learnt in English to another language. Multilingual learners have the necessary building blocks to achieve language-concordant care, but the complex skills to adapt and transfer knowledge and interpersonal communication skills across linguistic and cultural contexts must be longi-tudinally taught, evaluated and supported. Language should not be a mostly invisibleattribute that others uncover when conve-nient for them (‘Will you interpret for me in room 4?’). Rather, it is time to pay atten-tion to language as an aspect of identity that is also a critical professional tool to be harnessed in the service of patients. Informed by a growing body of research on language equity in medical education, I developed figure 2 to summarise evidence- based strategies for collecting and using physician language proficiency data to guide educa-tional opportunities for learners motivated to care for underserved linguistic groups.

In a busy ED or graduate medical education programme, it is easy to overlook invisible aspects of a patient or a learner’s life, such as language. Uncovering the linguistic capital in our midst—through intentional efforts to support and incentivise language skills that address population needs—may be key to making an accurate diagnosis, creating a treatment plan that a patient can fully understand and building a clinical learning environment where all learners are truly seen.